Abstract

In India, individuals who are incarcerated face an astoundingly high disease burden. Although Indian law guarantees those who are incarcerated a right to health and healthcare, conditions within Indian prisons flout this law. Given this, why haven’t Indian medical personnel called for change? We surmise that perhaps they simply are not aware of conditions in Indian prisons. In order to assess this conjecture, we conducted a pilot survey with senior students from one of India’s premier medical schools to assess the knowledge and attitudes of students toward the health-related rights, burdens, and conditions faced by Indian incarcerated individuals. We found that medical students were misinformed regarding the lack of medical services available to incarcerated individuals. Additionally, medical students frequently expressed opinions about the health and well-being of incarcerated individuals that do not comport with international codes of ethical conduct. Our findings suggest that Indian medical schools may not offer much if any education to medical students about ethics and human rights as they pertain to the rights of incarcerated individuals, and that more instruction is necessary so that the Indian medical community could begin to advocate for the rights of those held in Indian prisons.

It is said that no one truly knows a nation until one has been inside its jails. A nation should not be judged by how it treats its highest citizens, but its lowest ones.

— Nelson Mandela

Prisoner Rights & Prison Conditions in India

Incarcerated individuals in Indian prisons are, according to the Indian Constitution, entitled to fundamental protections. In the case of Sunil Batra vs. the Delhi Administration in 1980, the Indian Supreme Court ruled that individuals who are incarcerated do not lose their status as persons and maintain the same fundamental rights as anyone else. [1], [2] In fact, multiple rulings have determined that prisoners in India retain all the rights enjoyed by a free citizen, except for those that are obviously lost as a result of imprisonment, such as the freedom to travel freely across borders or the right to practice a profession. [3], [4], [5] Some of these rights include the right to a speedy and fair trial, the right to free legal aid, the right against cruel and unusual punishment, the right to live with human dignity, and the right to medical care. [6], [7] In the case of Parmanand Katara vs. Union of India, the Supreme court ruled that, “The patient, whether he be an innocent person or a criminal liable to punishment under the laws of the society, it is the obligation of those who are in charge of the health of the community to preserve life so that the innocent may be protected and the guilty may be punished.” [8]

Despite this and other rulings, the reality is that the majority of incarcerated individuals in India lack access to adequate, if any, medical or mental health care from health care professionals. In fact, the lack of access to health care is just one way in which the rights of prisoners in India are violated. In addition, those in Indians prisons generally have difficulty receiving a trial or being granted bail, are housed in substandard and harsh conditions, and face inhumane methods of solitary confinement. [9]

On average, Indian prisons are over 150 percent of their capacity, with some prisons being overcrowded at over 600 percent of their carrying capacity. [10] The principle reason for this rampant overcrowding is pre-trial detention, which is known in India as being “undertrial.” [11] According to the Prison Statistics India 2016 report, approximately 67 percent of all imprisoned individuals in India were ‘undertrial’ at the time], which is a significantly higher proportion than countries such as the UK (11 percent) and USA (20 percent). [12], [13] In general, those who are undertrial are poor, uneducated (42 percent had a literacy profile below Grade 10), accused of minor violations of the law, and unable to access legal or financial aid. [14]

In these overcrowded prisons, the facilities provided to prisoners are unhygienic and detrimental to their health and well-being. Indian prisons have been consistently criticized for their deplorable conditions by human rights activists who cite widespread unsanitary conditions, [15] including a shortage of toilets and urinals, dirty drinking water, lack of nutritious or hygienic food (in some instances meals were even infected with insects), shortages of sanitary napkins for women, and generally unhygienic living quarters. [16], [17], [18] All of these factors directly and adversely affect the physical and mental well-being of prisoners, and the health complications that arise as a result of these conditions are almost innumerable.

Prisoner Health

Given the discussion above, it is not surprising that incarcerated individuals in India are subject to a plethora of health conditions, ranging from communicable diseases to mental health disorders. Overcrowded and unsanitary conditions have made Indian prison environments extremely susceptible to the transmission of infectious diseases, including sexually transmitted diseases, such as hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV-AIDS, as well as diseases such as tuberculosis.

Studies have found rates of HIV prevalence in Indian prisons ranging from 0.5 percent-6.9 percent depending on the location. [19] A more recent preliminary study by the National AIDS Control Organization found that 2.5 percent of prisoners across 15 prisons were HIV positive, compared to a national HIV prevalence in the general population of 0.32 percent in males and 0.22 percent in females. [20], [21] High rates of HIV among incarcerated Indians are thought to be driven by the frequent sharing of needles for drug usage and by acts of unprotected sex between prisoners. [22] Upon finding that homosexual sex was prevalent among almost 90 percent of male prisoners at one jail in India, the Indian Council of Medical Research recommended providing condoms to prisoners. [23] But because acts of homosexuality are considered illegal under Indian law, the provision of condoms to those who are incarcerated was neither accepted nor practiced as an AIDS prevention measure until 2018, even though stigma and homophobia remain rampant in India. [24]

Screening and treatment services for tuberculosis (TB) are also not optimal in the context of Indian prisons. According to the World Health Organization, prison populations are a ‘tuberculosis risk group’, which should receive systematic screening for protection. [25] A 2017 study conducted in 157 Indian prisons found that only 50 percent of prisons screened new inmates at time of entry and only 59 percent carried out regular or periodical screening. [26] The same study also found that 19 percent of those screened had TB symptoms and nearly 8 percent were diagnosed with TB on microscopy. A 2013 cross sectional study of a South Indian jail found that nearly 10 percent of inmates suffered from acute upper respiratory tract infections, 18 percent had ascariasis, and 84 percent had anemia. [27]

Rates of mental health disorders are also substantially higher amongst Indian prisoners than the rest of the population. One study found that 23.8 percent of convicted individuals suffered from psychiatric illness excluding substance abuse, and 56.4 percent had a history of substance abuse or dependence prior to incarceration. [28] A survey by the National Institute of Mental Health & Neuro Sciences found that rampant negligence by prison staff, in conjunction with other human rights violations, have led to an increase in the incidence of mental instability amongst prisoners in India. [29] According to a statement by the Indian home ministry in 2016, 11 percent of prisoners died of unnatural causes, such as “suicide, execution, murder by inmates, . . . deaths due to negligence/excess by jail personnel and others.” [30] The number of unnatural deaths varies according to which prison system is being considered. On the worst end of the spectrum, Odisha prisons reported an increase of 1,367 percent in unnatural deaths over a period of four years. [28]

Torture is also common in Indian prisons, the effects of which are strongly linked to a host of adverse psychological and physical sequelae, including death. [31] A landmark report released by the Asian Centre for Human Rights collated evidence of 1,504 deaths in police custody and 12,727 deaths in prison over a 10-year period, and stated “99 percent of deaths in police custody can be ascribed to torture and occur within 48 hours of the victims being taken into custody.” [32] "Torture remains endemic, institutionalised, and central to the administration of justice and counter-terrorism measures," the Asian Centre for Human Rights said. In one particular facility, Cellular Jail (Port Blair), punishment routinely included working in chains. If inmates objected, they were made to stand handcuffed to the wall for 7 days. [33] Reports from Tihar Jail (Delhi) detail the mass beating of inmates during regular inspections, often resulting in severe injuries needing surgical attention. [34] A case in Byculla Jail (Mumbai) garnered national attention, wherein a woman who complained about food was brutally beaten and raped by prison guards, and eventually died. [35] Prisoners on death row are routinely subjected to torture, with inmates recalling experiences “being hung by wires, being forced to drink urine, being placed on a slab of ice, having a leg broken, forced anal penetration, and extreme stretching, being tied in a sack of chillies and beaten with the butts of police guns.” [36] The upshot from all of these reports is that torture in Indian prisons by prison authorities is omnipresent, extreme, and particularly harmful to the health and well-being of incarcerated individuals.

Access to Healthcare & Medical Obligations

India, as a whole, experiences a significant shortage of physicians. Although the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a doctor to patient ratio of 1:1000, the ratio of doctors to patients in India is 1:1674. [37] Thus, India needs 500,000 more physicians for the entire country than the amount that is currently practicing in order to meet the WHO standard. [37] Given this reality, it is unfortunately not surprising that there are physician shortages in Indian prisons and jobs in prisons for medical personnel are going unfilled. For example, as of 2016 in Karnataka, 12 out of 18 jobs posted for prison medical officers, and 2 out of 2 jobs posted for prison psychiatrists, were not filled and remained vacant. [38] Its largest jail, the Parappana Agrahara Jail which contains 4,400 prisoners, only had two doctors on its payroll. [38] According to the Maharashtra Director General of Police, a lack of full-time doctors was the single biggest problem facing district jails and prisons. [39] Human rights activists have made similar claims regarding Hyderabadi jails, which have also been reported to have vacant job postings and inmates lacking avenues for routine medical care. [40] Similar claims have been made by advocates regarding medical employment in Tamil Nadu as well. [41]

The consequences of all of the above is that incarcerated individuals in India form an extremely underserved section of the population with regard to access to healthcare and health services. What is more, the majority of prisoners are uneducated, poor, and belong to marginalized or socially disadvantaged groups, representing a distinct health group needing priority attention due to their vulnerable status and limited knowledge about health. [42]

Given the dire circumstances faced by incarcerated individuals in India, it seems reasonable to ask how much Indian physicians are aware of the difficulties and hardships faced by prisoners in their country. How much are Indian physicians educated about the plight of Indian prisoners and what are their thoughts about these matters? And do Indian physicians harbor biases about prisoners? After all, given that physicians are themselves a part of a larger societal community, physicians may not be free from the biases that exist regarding prison populations. Such bias might be especially likely if physicians have not been adequately taught about the disadvantages and distinct health needs of those who are incarcerated.

To our knowledge, there have been no studies about medical students’ or physicians’ awareness about, or attitudes toward, prison populations in India. Given this lack of information, we sought to conduct a pilot study in order to assess the knowledge and attitudes of the emerging physician workforce in India towards prisoner health. Through our survey, we hoped to assess medical students’ general knowledge and awareness about prisoner health, rights, and prison environment. Additionally, we sought to assess medical students’ attitudes and opinions with respect to the extent of medical and ethical obligations towards incarcerated individuals, and physician involvement in the health of incarcerated individuals.

Pilot Survey

We developed a two-part pilot survey for Indian medical students that allowed us to evaluate the level of general knowledge and attitudes of medical students with regards to prisoner health and human rights. Part I of the survey (Appendix 1) included questions about how many hours of prison health education participants had received; general knowledge of Indian prisoners’ access to preventative, emergency, and mental health care services; knowledge of health risks and living conditions faced by Indian prisoners; and knowledge about the state’s obligation towards the health of prisoners in their country. Part II of the survey (Appendix 1) included questions about participants’ general attitudes towards health care access for prisoners who committed low-grade or high-grade crimes; whether or not prisoners should have access to treatment for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), contraceptives, mental health services, medication and counselling for alcohol and drug addiction, and exercise facilities; whether or not it is permissible for prisoners to be kept in solitary confinement and for prison officials to use manipulation tactics; whether or not it is morally permissible for physicians to refuse to treat prisoners based on the nature of their crime, or to take part in capital punishment; if they would be willing to serve prison populations as physicians; and if physicians should receive education about prison health in medical schools.

The survey was distributed in paper format, in English, to medical students who were in their final year of their Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS) degree, at the end of a regularly scheduled class in one of India’s premier medical schools. No identifying information was collected, and the survey responses were recorded and tabulated in Microsoft Excel in a data file and analyzed accordingly. The study was exempted by the Cambridge Health Alliance Institutional Review Board in Cambridge, MA, United States.

Survey Findings

All students who attended class when the surveys were distributed elected to fill out the survey (response rate: 100 percent, N=98). The vast majority (91.8 percent) of students reported receiving less than 1 hour of education regarding prisoner health and access to health care, with 8.2 percent responding that they received 1-5 hours. No students had received more than 5 hours of such education.

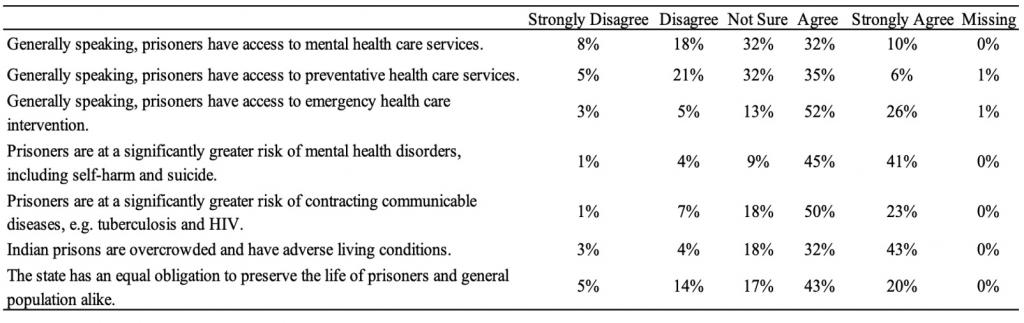

Participants’ general knowledge of incarcerated Indians’ access to healthcare services and prison conditions are shown in Figure 1. Forty-two percent agreed (32 percent agreed, 10 percent strongly agreed) that prisoners generally had access to mental health care and 32 percent were not sure. Similarly, when asked whether prisoners have access to preventative care services, 41 percent agreed (35 percent agreed, 6 percent strongly agreed) and 32 percent were not sure. When respondents were asked if prisoners receive emergency healthcare intervention, 78 percent agreed (52 percent agreed, 26 percent strongly agreed). The majority of respondents agreed that prisoners are at a greater risk of developing mental health disorders including self-harm and suicide (86 percent; 45 percent agree, 41 percent strongly agree) and contracting communicable diseases such as tuberculosis and HIV (73 percent; 50 percent agree, 23 percent strongly agree).

Most students seemed to be aware of the abhorrent conditions facing incarcerated individuals in India, with 75 percent agreeing that prisons are overcrowded and have adverse living conditions. When asked whether the state has an equal obligation to preserve the life of prisoners and the general population, 63 percent agreed (43 percent agree, 20 percent strongly agree), 17 percent were not sure, and 19 percent disagreed (15 percent disagree, 4 percent strongly disagree).

Table 1. Results from Part One of Pilot Survey: Indian medical students’ knowledge regarding prisoners’ rights, health, and prison conditions in India.

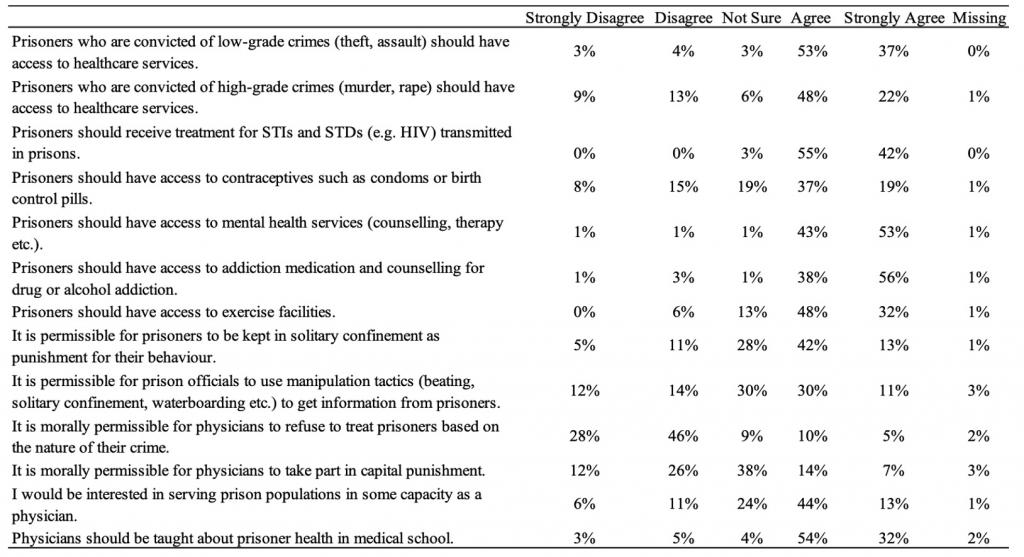

Students’ attitudes towards health care access and their role in providing that care for Indian incarcerated individuals are shown in Figure 2. When asked whether prisoners who committed low-grade (LG) crimes (theft, etc.) and high-grade (HG) crimes (murder, rape, etc.) should receive health care access, more agreed that low-grade criminals have a right to health care than high-grade (90 percent LG, 70 percent HG), and more disagreed that high-grade criminals should receive health care than low grade (19 percent HG, 7 percent LG), with a similar amount being unsure for both (6 percent LG, 3 percent HG). When asked about more specific health care services for prisoners, the vast majority respondents agreed that prisoners should have access to treatment for STD’s and STI’s (97 percent), mental health services (96 percent), medication and counselling for alcohol and drug addiction (94 percent), and exercise facilities (80 percent). There was much more disagreement and uncertainty, however, for whether or not prisoners should receive access to contraceptives such as condoms or birth control (56 percent agree, 23 percent disagree, 19 percent not sure).

With respect to students’ level of moral acceptance and the permissibility of certain treatment of prisoners, 55 percent agreed that solitary confinement was acceptable as a punishment for their behaviour, whereas 28 percent were not sure. Similarly, 30 percent were unsure about the acceptability of employing coercive traumatic tactics (beating, waterboarding, etc.), although responses more evenly spread with 41 percent agreeing that such methods were acceptable and 26 percent disagreeing. In addition, responses to whether or not it is morally permissible for physicians to take part in capital punishment were also fragmented, as 21 percent were not sure, 38 percent disagreed, and 38 percent agreed. When respondents were asked whether it was morally permissible for a physician to refuse to treat someone based on the nature of their crime, the majority (74 percent) responded that it was not morally permissible. However, 15 percent thought that it was morally permissible and 9 percent were unsure.

Perhaps because of how little education they actually receive about these matters, a significant majority of students agreed (86 percent) that physicians should receive education about prison health in medical schools. Furthermore, 57 percent of the respondents say they would be interested in serving as a physician for prison populations at some point in the future.

Table 2. Results from Part Two of Pilot Survey: Indian medical students’ attitudes and values regarding prisoners’ rights and health in India.

Discussion

Our survey findings suggest that Indian medical schools may not offer much if any education to medical students about prisoner rights pertaining to healthcare and conditions in Indian prisons. Indeed, a Principal at an Indian medical school (other than the one we surveyed) stated emphatically that there is no education in Indian medical schools about these matters. Given the health crisis within Indian prisons, our findings are concerning given that the Indian medical community could – and we would argue ought to – offer a strong voice in support of prison reform.

The lack of knowledge that medical students have regarding prisoners’ health burdens and healthcare access is understandable given the lack of specific education that medical students receive about the prison population. This lack of knowledge likely also contributes to the relative silence of the Indian medical community about the horrid health conditions faced by incarcerated individuals in India. No matter the reason, the general lack of awareness regarding basic human rights is concerning. We believe that it is essential that medical students are able to recognize basic human rights violations such as torture and solitary confinement. This is perhaps even more important in India where those who are incarcerated routinely have basic human rights flouted and regularly experience torture. Physicians are uniquely positioned to advocate against these practices and should be the ones leading the call for health and human rights for prisoners, and if future physicians receive little or no education about these matters they are ill-positioned to provide such advocacy.

Some might argue that prisoners deserve to endure the harsh conditions found in Indian prisons. For those who take this position, we offer three important reminders: first, the vast majority of the prison population in India have not been convicted of any crimes but are in fact awaiting trial. Therefore, many individuals who are forced to endure unhealthy conditions and torture are fully innocent. Second, the vast majority of those who are held in Indian prisons will eventually reintegrate into society, carrying their mental health and disease burdens back into the public, so attending to their health while they are incarcerated is in fact attending to the health of the general public. Third, the conditions that incarcerated individuals face in Indian prisons are not only immoral, but also illegal according to both Indian and international law.

Our findings are encouraging given that respondents held favourable attitudes towards prisoners having access to resources that are scarcely available and oftentimes culturally considered taboo (e.g. counselling, addiction medication, exercise facilities, treatment for STDs, and contraceptives). In addition, an overwhelming majority of respondents agreed that prisoners should receive treatment for STDs/STI’s, and a small majority felt that contraceptives should be made available as well. Access to contraceptives has been a source of controversy and debate in the Indian medical community for many years given India’s long history of stigma regarding homosexuality. The liberal attitudes displayed by the respondents, in contrast to historical norms and mores, are encouraging in that the future physician workforce is perhaps more resistant to traditional cultural norms and beliefs.

Prison health reform is not a simple task, but one place to start is to ensure that those who are in a position to advocate on behalf of reform are knowledgeable about the realities facing those who are incarcerated in India. Promisingly, medical students in our pilot survey clearly wanted more education about these matters. A significant majority of respondents indicated that they believe that prisoner health should be taught in the medical curriculum and that they would be interested in working in prison populations. It is reasonable to then assume that more education surrounding health issues faced by Indians who are incarcerated would be in the students’ academic interests and also of practical value to their future practice. Integrating courses, seminars, rotations, or internships in prison health into medical school curriculums would, at minimum, provide a more accessible path for students to work with an underserved population like those who are incarcerated.

Our pilot survey understandably has limitations. First, this survey is limited to medical students at a single Indian medical school, representing a very small portion of the future physician workforce in India. Despite this limitation, we have no reason to believe that education at the medical school we surveyed is significantly different from education at other medical schools in India. Indeed, this school is a flagship medical school in India that other medical schools likely look to in order to emulate. Regardless, future studies should sample students at various medical schools around India in order to accurately portray the landscape of medical training as it pertains to these matters. Another limitation is that we do not know if increasing education about human rights and the health of incarcerated individuals will necessarily lead to more physicians working in prisons or advocating for change.

In conclusion, achieving progress with respect to prisoner rights and health is generally difficult given the lack of empathy that is usually accorded to those who are incarcerated. In resource-poor countries, lack of resources only compounds matters given this prevailing attitude. Despite these realities, India is taking steps to increase spending on public health resources and aims to increase spending in this area to 2.5 percent of its gross domestic product by 2025. [43] This increase in spending is a step in the right direction, and we believe that a portion of this increase ought to be allocated to Indian prisons, given that those incarcerated in Indian prisons and jails currently face health and living issues that not only dangerously impact their own health and well-being, but that of the entire Indian society. We believe that the Indian medical community ought to advocate for and promote the health and human rights of prisoners in India and providing instruction during medical education could make such advocacy more likely.

Authors Affiliations:

Shivam Singh1, Farhad R. Udwadia1,2, Shayan Sadeghieh3, J. Wesley Boyd1,4

1 Center for Bioethics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

2 Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

3 Department of Engineering, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom

4 Department of Psychiatry, Cambridge Health Alliance, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA

Corresponding Author:

Farhad R. Udwadia, MBE

farhad.udwadia@alumni.ubc.ca

Acknowledgement:

We would like to thank Andrew Medeiros and Isabelle Ghelerter at McGill University for their helpful comments and assistance with the data analysis.

References

[1] Lokur MB. "Re: Inhuman Conditions in 1382 Prisons… vs State of Assam on 13 December, 2018." Supreme Court of India. Decmber 13, 2018. https://indiankanoon.org/doc/143664436/.

[2] Sunil Batra v. Delhi Administration, 2 SCR 557 (1980). Supreme Court of India. https://indiankanoon.org/doc/778810/.

[3] T.V. Vatheeswaran v. State of Tamil Nadu, 2 SCR 348 (1983). Supreme Court of India. https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1536503/.

[4] State of Andhra Pradesh v Challa Ramkrishna Reddy & Ors, 5 SCC 7123 (2000). Supreme Court of India. https://indiankanoon.org/doc/731194/.

[5] Kothari, Saurbh. "Taking Prisoner Rights Seriously." Legal Service India (New Delhi, India) http://www.legalserviceindia.com/articles/po.htm.

[6] Kumar, Ritesh. “Rights of Prisoners under Indian Law." Legal Desire Media and Insights. September 15, 2017. www.legaldesire.com/rights-prisoners-indian-law/#_ftn1.

[7] Jain, Riya. "Article 21 of the Constitution of India - Right to Life and Personal Liberty." Lawctopus (Chandigarh, India) November 13, 2015. www.lawctopus.com/academike/article-21-of-the-constitution-of-india-right-to-life-and-personal-liberty/#_edn81.

[8] Parmanand Katara v. Union Of India & Ors, 3 SCR 997 (1989). Supreme Court of India. https://indiankanoon.org/doc/498126/.

[9] Gonsalves, Colin. 3rd National Consultation on Prisoners' Rights, Legal Aid, and Prison Reform. New Delhi: Human Rights Law Network (HRLN), April 4, 2016. https://hrln.org/publications/national-consultation-on-prisoners-rights-legal-aid-and-prison-reform-2016/. Accessed August 2019.

[10] PTI. "India: overcrowding prisons a violation of human rights, says Supreme Court." The Hindu (Chennai, India) May 13, 2018. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/overcrowded-prison-involves-violation-of-human-rights-says-worried-supreme-court/article23871465.ece. Accessed August 2019.

[11] Rath, Basant. "Why We Need to Talk About the Condition of Indian Prisons." The Wire (New Delhi, India) July 26, 2017. https://thewire.in/uncategorised/india-prison-conditions.

[12] Government of India; Ministry of Home Affairs. Prison Statistics India 2016; Executive Summary. New Delhi, India: National Crime Records Bureau, updated May 12, 2019. http://ncrb.gov.in/sites/default/files/Executive%20Summary-2016.pdf. Accessed August 2019.

[13] Dubuddu, Rakesh. "Indian Prisons are Overcrowded & 2/3rd of the Inmates are Under Trials." Factly (Telegana, India) April 25, 2015. https://factly.in/indian-prisons-are-overcrowded-23rd-of-the-inmates-are-under-trials/.

[14] Government of India; Ministry of Home Affairs. Prison Statistics India 2016. New Delhi, India: National Crime Records Bureau, updated May 12, 2019. http://ncrb.gov.in/prison-statistics-india-2016. Accessed August 2019.

[15] Human Rights Watch. Prison Conditions in India. New York, NY: Human Rights Watch website, 1991. https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/INDIA914.pdf. Accessed August 2019.

[16] Setalvad, Teesta. "Women prisoners recount Jail Horror stories." Citizens for Justice and Peace (CJP). January 24, 2019. https://cjp.org.in/women-prisoners-recount-jail-horror-stories/.

[17] CJP Team. "Plight of Women in Indian Prisons." Citizens for Justice and Peace (CJP). March 9, 2019. https://www.globalresearch.ca/plight-women-indian-prisons/5671481.

[18] Nagda, Priyadarshi. "A Socio-legal Study of Prison System and its Reforms in India." Mohanlal Sukhadia University, Faculty of Law, 2016. https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/147761/1/priyadarshi%20nagda.pdf.

[19] Dolan, Kate and Sarah Larney. "HIV in Indian prisons: Risk behaviour, prevalence, prevention & treatment." Indian Journal of Medical Research 132, no. 6 (2010): 696-700.

[20] Rao, Menaka. "Unsafe sex and drug use in India's prisons is leading to high HIV rates." Scroll.in January 22, 2018. www.scroll.in/pulse/865861/high-levels-of-hiv-hepatitis-c-and-tb-found-among-prison-inmates-in-india.

[21] Government of India, Press Information Bureau (PIB). HIV Estimations 2012 Report Released. New Delhi, India: Press Information Bureau, 2012. www.pib.nic.in/newsite/printrelease.aspx?relid=89785.

[22] Bhattacharya, Priyanka. "Indian prisons becoming HIV haven." NDTV (New Delhi, India) April 8, 2009. www.ndtv.com/india-news/indian-prisons-becoming-hiv-haven-390929.

[23] UPI Archives. “Condoms recommended for India jails.” United Press International (UPI) (Washington, D.C.) February 28, 1995. www.upi.com/Archives/1995/02/28/Condoms-recommended-for-India-jails/1802793947600/.

[24] Misra, Geetanjali. "Decriminalizing homosexuality in India." Reproductive Health Matters 2009;17, no. 24 (2009): 20-28.

[25] World Health Organization. Systematic Screening for Active Tuberculosis: Principles and Recommendations. Geneva, Switzlerand: World Health Organization; 2014. https://www.who.int/tb/publications/Final_TB_Screening_guidelines.pdf.

[26] Prasad, Banuru Muralidhara, Badri Thapa, Sarabjit Singh Chadha, Anand Das, Entoor Ramachandra Babu, Subrat Mohanty, Sripriya Pandurangan, and Jamhoih Tonsing. "Status of Tuberculosis services in Indian Prisons." International Journal of Infectious Diseases 56 (2017): 117-121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2017.01.035

[27] Kumar, Sunil D., Santosh A. Kumar, Jayashree V. Pattankar, Shrinivas B. Reddy, and Murali Dhar. "Health Status of the Prisoners in a Central Jail of South India." Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine 35, no. 4 (2013):373-377.

[28] Goyal, Sandeep Kumar, Paramjit Singh, Parshotam D. Gargi, Samta Goyal, and Aseem Garg. "Psychiatric morbidity in prisoners." Indian Journal of Psychiatry 53, no. 3 (2011): 253-257. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.86819

[29] Rao, Kamalapathi H. "South Indian jails top mentally ill prisoners' list." Deccan Chronicle. (Secunderabad, India) October 15, 2017. www.deccanchronicle.com/nation/current-affairs/161017/south-indian-jails-top-mentally-ill-prisoners-list.html.

[30] Grocchetti, Silvio. "Death behind bars: 1,700 died in overcrowded Indian prisons in 2014." Scroll.in. January 3, 2017. www.scroll.in/article/816678/death-behind-bars-1700-died-in-overcrowded-indian-prisons-in-2014.

[31] De C Williams Amanda C. and Jannie van der Merwe. "The psychological impact of torture." British Journal of Pain 7, no. 2 (2013): 101–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/2049463713483596

[32] Randolph, Eric. "Human rights report says 14,000 Indian prison deaths in a decade." The National (Abu Dhabi, UAE) November 23, 2011. www.thenational.ae/world/asia/human-rights-report-says-14-000-indian-prison-deaths-in-a-decade-1.441995.

[33] Chaudhary, Paurush. "Inside 5 Of India's Deadliest Prisons." India Times (Bombay, India) July 4, 2017. www.indiatimes.com/news/india/they-are-supposed-to-be-rehabilitation-centres-but-these-5-prisons-turn-every-prisoners-life-into-a-nightmare-234551.html.

[34] Nigam, Chayyanika. "Tihar jail torture: Staffers suspended over allegations of 'merciless' beatings against prison inmates." Daily Mail Online (London, U.K.) December 1, 2017. www.dailymail.co.uk/indiahome/article-5134585/Tihar-jail-torture-Staff-suspended-allegations.html.

[35] Doshi, Vidhi. "A brutal sexual assault sparked riots in an Indian prison. Reports focused on a celebrity inmate instead." The Washington Post (Washington, D.C.) June 28, 2017. www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2017/06/28/an-inmate-was-brutally-assaulted-in-an-indian-prison-sparking-a-riot-but-media-coverage-has-turned-her-death-into-a-footnote/?utm_term=.48c6a33ed93a.

[36] Death Penalty Research Project, Project 39A. Death Penalty India Report Summary. Death Penalty Research Project. May 6, 2016. https://www.project39a.com/dpir.

[37] Indiaspend Team. "Healthcare crisis: Short of 5 lakh doctors, India has just 1 for 1,674 people." Hindustan Times (New Delhi, India) September 1, 2016. www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/healthcare-crisis-short-of-5-lakh-doctors-india-has-just-1-for-1-674-people/story-SZepTyjJ78WgOVIo93tBVK.html.

[38] Yadav, Umesh. "4,000 inmates but only two doctors in Bengaluru's prison." The Economic Times (Mumbai, India) August 17, 2016. www.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/4000-inmates-but-only-two-doctors-in-bengalurus-prison/articleshow/53735090.cms.

[39] Rajput, Rashmi. "Overcrowding, lack of staff and doctors biggest problems, says Bhushan Kumar Upadhyay." The Indian Express (Mumbai, India) July 13, 2017. www.indianexpress.com/article/cities/mumbai/overcrowding-lack-of-staff-and-doctors-biggest-problems-says-bhushan-kumar-upadhyay-byculla-4749590/.

[40] Rao, Victor. "Lack of doctors hits Hyderabad prisons." The Hans India (Hyderabad, India) March 3, 2015. www.thehansindia.com/posts/index/2015-03-03/Lack-of-doctors-hits-Hyderabad-prisons-134938.

[41] Nadar, A. Ganesh. "Why are prisoners dying in Tamil Nadu prisons?" Rediff (Mumbai, India) April 6, 2016. www.rediff.com/news/interview/why-are-prisoners-dying-in-tn-prisons/20160406.htm.

[42] Bhaumik, Soumyadeep and Rebecca J. Mathew. "Health and beyond…strategies for a better India: using the “prison window” to reach disadvantaged groups in primary care." Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care 4, no. 3 (2015): 315–318. https://doi.org/10.4103/2249-4863.161304.

[43] "India to increase public health spending to 2.5% of GDP: PM Modi." The Economic Times (Mumbai, India) December 12, 2018. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/policy/india-to-increase-public-health-spending-to-2-5-of-gdp-pm-modi/articleshow/67055735.cms.