“Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist in the United States…”

—13th Amendment, United States Constitution

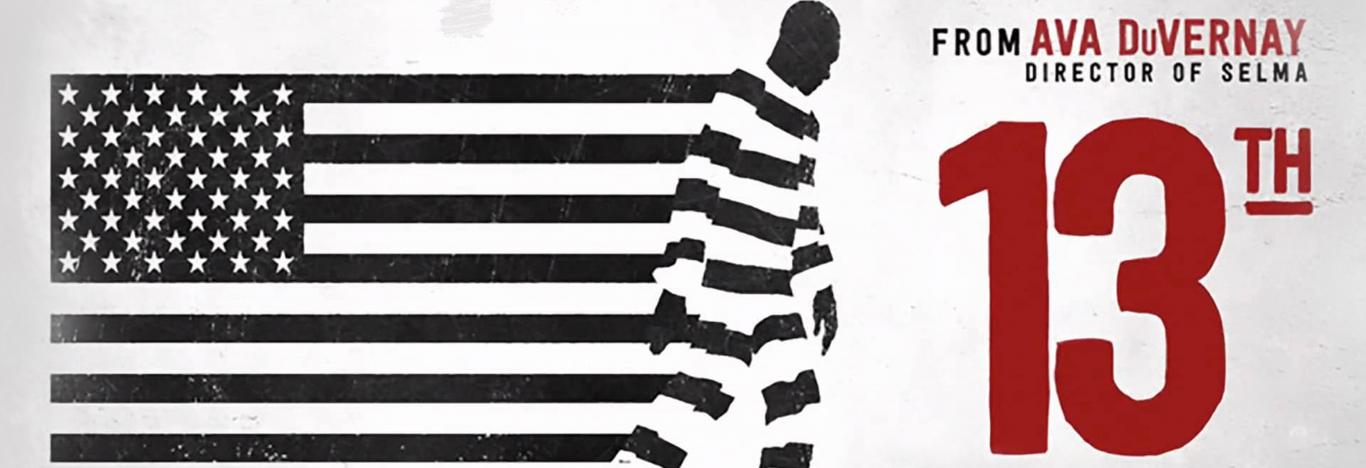

The United States has the highest rate of incarceration in the world, currently housing 2,220,300 people—twenty-five percent of the world’s prisoners. Director Ava DuVernay examines the promise of American freedom endowed by the 13th Amendment in her award-winning documentary 13th. [1] The film uses commentary from scholars, legislators, and political activists to explain how mass incarceration in the United States, through decades of cultural and political shifts, became a legal extension of slavery. 13th has advanced the normative conversation about race in the United States, by rendering a new conception of mass incarceration—and the policies and social structures that were established to support and normalize it.

Although it is understood that slavery was morally repugnant, there was something that also made it historically permissible. This something, referred to as “a cancer” in 13th, is a useful analogy in examining social injustice. First, this reference to cancer allows us to consider the insidious nature of this "social disease." Once the diagnosis has been made, it can be expected that, without treatment, this tumor will mutate and spread. Similarly, the racial divide in the United States was inherent in the county's birth. It is not something new, and in fact the current system of incarceration and society as a whole, can be accurately recognized as a permutation of these previous injustices. Next, the use of medical language in this context opens a previously inaccessible way of understanding and relating to the deeply subjective, personal, and painful experience of injustice. On the social level, we are given a framework for understanding how this disease metastasizes in society. By framing mass incarceration as a cancer, the issue is not only expressed in moral terms but can be read as a bioethical issue with real-world health implications.

“We did not cut out this cancer.”

Former U.S. Representative Charles B. Rengel, 13th

In 1854, future President Abraham Lincoln acknowledged that the country's founders used excused themselves from their responsibility to address slavery's malign nature by claiming they had merely inherited the institution and the problems it had created for the union. At a campaign speech in Illinois, Lincoln himself framed slavery as a cancer:

The thing [slavery] is hid away, in the constitution, just as an afflicted man hides away a wen or a cancer, which he dares not cut out at once, lest he bleed to death; with the promise, nevertheless, that the cutting may begin at the end of a given time.” [2]

Lincoln's application of a medical metaphor to slavery reveals the deep understanding of racial injustice as real a threat to the health of the nation as an untreated cancer is to the health of an individual. This conception, as proven by its reference in 13th, remains a relevant framework in describing the modern carceral system. Although many today recognize the moral repugnance of slavery, in the same sense that Lincoln described the "afflicted man," we remain ambivalent about agressive forms of treatment. Similarly, there is reluctance to engage in radical change around criminal justice reform. The deeprooted racism stokes fears that removing the cancer in its entirety, risks the total demise of our society. 13th posits that it is this fear that informed policies—from on abolition were written, and warns that myopic imagination keeps the cancer alive.

13th contextualizes the abolition of slavery as so controversial that it led to civil war. Congress passed the 13th Amendment in January 1865, and it was ratified in December 1865, about five months after the Civil War ended. Although the Amendment made involuntary servitude unconstitutional, freedom was not afforded to those convicted of a crime.

The film presents the 13th Amendment as a repackaging—a mutation—of the social and political structures that held slavery in place by redefining criminal behavior during the Reconstruction period and creating criminal policy that targeted newly freed slaves. Immediately after the Civil War, freed slaves without homes or work were arrested en masse on suspicious persons, loitering, and vagrancy charges. “Black codes” and “Pig Laws,” which preceded Jim Crow laws, denied rights to Black people, inoculating the daily experiences of newly freed slaves with immense difficulty. Labeled “criminal” and subsequently imprisoned, these individuals were then repurposed to rebuild the economy as slave laborers through the carceral state.

Writer Jelani Cobb argues in 13th that the myth of Black criminology was born during this wave of Reconstructionist mass imprisonment. Drawing on the 1915 movie The Birth of a Nation —in which black men were depicted as animalistic, vulgar, and violent, while white women were portrayed as the fragile subjects of imagined black violence—Cobb argues that the film was as an important cultural catalyst that has been undervalued for its role in developing misconceptions about race that continue to be perpetuated. In the film’s wake came the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan’s terrorism, including the socially legitimated lynching of black men. The myth of Black criminology applied to normal human behavior, authorized the targeted prosecution of people of color, and made doing so moral in the white social imagination. Social imagination begets public action, and a new form of slavery began.

“We’re always going to see new permutations of a cancer, right? And that’s what this is.”

—Gina Clayton, 13th

Over time, the cancer, rooted in slavery, continued to spread and mutate. “So many aspects of the old Jim Crow are suddenly legal again, once you’ve been branded a felon,” said Michelle Alexander, a commentator in 13th. In the 1970s and ‘80s, political leaders declared drugs and addiction to be enemies of the public and passed mandatory minimum sentencing laws for crack—though not for powder cocaine, which was considered a drug of the affluent. The focus on crack, used more often in Black communities, effectively removed Black men from families and communities. According to a Department of Justice report, eighty-eight percent of those convicted of crack-related convictions were Black.

Through mandatory minimum sentencing laws in the 1980s and 90s, legislators stepped around judicial discretion in sentencing, instead putting that power into the hands of prosecutors. Forced to choose between a double-digit sentence and trial, the accused often agreed to plea-bargaining. This coercive mechanism has changed the landscape of justice: ninety-seven percent of the prison population has been incarcerated due to plea bargains, not convictions. The accused seldom see their day in court. Three-strikes legislation, truth in sentencing, and the omnibus 1994 Crime Bill provided perverse incentives to expand incarceration by giving billions of dollars in grants for community policing and the employment of over 100,000 new officers. A federal “three strikes” provision and billions in state grants were given to build new prisons to enforce truth in sentencing laws that required at least eighty percent of a sentence be served. Nine states adopted three-strikes laws, and twenty-one states amended existing laws to get the funding, with a final tally of forty-two states having such laws in compliance with the crime bill.

These policy shifts, Michelle Alexander argues in the film, are all part of the same system of oppression, and that system will only change when sustaining it is too expensive. But like plantation owners saw economic prosperity in the institution of slavery, corporations invested in the prison industrial complex. These companies are profiting significantly from the system of incarceration. Alexander argues that American politics privilege the lucrative nature of the prison business in the design of criminal justice programs. We have had little meaningful discussion about how to atone for the impact of persistent structural violence and psychic trauma that affect Black people, families, and communities across generations. We have had sought no means in good faith to remove the cancer.

“History is not just stuff that happens by accident.”

—Kevin Gannon, 13th

The metaphor of illness in 13th is useful in addressing the cancer within us, our communities, and our country. 13th provides a compelling argument that this disease, is known and has been known. In his book Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Michel Foucault gives a chronology of the concepts and practice of punishment and the ways in which systems sustain power. [3] He argues that biology itself is a powerful idea that can be and has been an instrument of social control. Foucault defines “biopower” as “the set of mechanisms through which the basic biological features of the human species become the object of a political strategy.” [4] Biopolitics, therefore, refers to the “apparatuses, strategies and techniques of government that are based on biopower.”

Foucault rejects that power is held at “the top,” arguing instead that power moves through the capillaries of society. The prison, therefore, is not the locus of power from which the subjugation of Black people stems. Rather, it is the carceral state, which receives its power from institutions, networks, and daily human behaviors that normalize the mechanisms of incarceration. Foucault argues that all institutions that compose society have as their fundamental objective to normalize, and biopower is critical to achieving this normalization. [4] 13th walks us through this normalization by organizing the features of society that gave rise to the asymmetrical system of mass incarceration. The film elicits just how powerful and harmful the system is.

Biopower is a helpful concept to think through the something that makes Black lives perpetually vulnerable to oppression, and it may help uncover how our current epistemological orientations—in science, biology, and medicine—may contribute to the cancer of incarceration.

We ought to explore how our biological features—skin color, gender, age—have operated as political mechanisms, with explicit (albeit not necessarily obvious) regulating abilities on populations and daily lives. For example, we are tasked with understanding how race became normalized as a science of difference, which folded into social context and policy, and mutated into the social order. We should interrogate how the institution of bioethics is working in ways that may continue to normalize mechanisms of social order, and we should strive to be disruptive when necessary.

This is but one theoretical approach we may consider turning to. Our efforts to rigorously understand our persistent cancer charge us with uncovering new ways of framing the problem and pioneering a new bioethics landscape to include such problems. Glenn E. Martin, interviewed in the film, argues that systems of oppression are durable and tend to reinvent themselves right under our noses. We face a formidable challenge when trying to understand mass incarceration. In bioethics, the scope of our role in social justice has yet to be defined. While we deliberate on the social determinants and realities of health and inequality, we must keep in the forefront of our minds that history, culture, and subjectivity frame the conditions we encounter. When confronting a bioethics problem that inherits centuries of injustice, we are reminded not to seek solutions that protect the cancer or absolve responsibility. We must be a vanguard for rehabilitating care and respect for humanity in ways that disrupt our cancer’s security. We must contemplate justice and create space for mercy and atonement in our work.

The sum of the efforts that we dedicate in this direction has the potential to slowly chip away at intolerable systems of inequality. While we shape the field of bioethics, we must take squarely into account the reality of mass incarceration, framing the issue in a way that empowers us to recognize history, instills in us the courage to lead, and inspires us to discover a cure.

Allyn Benintendi, BA, MBE ’18, can be reached at aobenintendi (at) gmail.com.

[1] DuVernay, Ava and Spencer Averick. 13th. Directed by Ava DuVernay (Netflix, 2016), Video file. https://www.netflix.com/title/80091741.

[2] Lehrman, Lewis E.. Lincoln at Peoria: The Turning Point. (Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books, 2008) 143.

[3] Michel Foucault. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. (New York: Pantheon Books, 1977).

[4] Michael Foucault. Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the College de France. (1977-1978).